Worley, H and Cochrane, H., 2024. Resistance to CAT - Reframed through the Polyvagal Theory Lens. Reformulation, Winter, p.24-25.

From Freud to present day, therapists frequently conceptualise and locate ‘resistance’ as client specific behaviours that impede progress (Ryland et al, 2021). This unhelpful perspective may not only threaten the therapeutic alliance, but more importantly it ignores the possibility that resistance can be located within any of us, including the therapist. Stephen Porges’s Polyvagal Theory (PVT) offers a bio-behavioural mechanism to explain and understand why human relatedness and the health of our nervous system is reliant on relational connections with people with whom we feel safe (Porges & Porges, 2023). The Polyvagal Theory enables the reframing of the concept of ‘resistance’ in therapy as an unconscious and automatic physiological response to how safe we feel.

The Polyvagal Theory describes how our Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) operates as our ‘autopilot’, unconsciously and defensively activating in response to perceived threats or conversely, downregulating these defences when we feel safe to encourage calmness, openness, and connection with others (Porges, 2011). According to The Polyvagal Theory, we all unconsciously employ a hierarchy of three autonomic states to assess environmental cues of safety or threat and adjust our behaviour accordingly (Porges, 2001, 2003, 2011).

The oldest evolutionary state, the Dorsal Vagal Complex State (DVC), responds to perceptions of extreme threat by shutting down, freezing, dissociating, or feigning death. The Polyvagal Theory posits that the ancient immobilisation or ‘freezing’ defence mechanism helps explain trauma reactions such as fainting, defecation and dissociation as the body’s response to extreme threat is not only psychological but physiological, with observable changes in the body. In this sense, trauma is not only in our mind but also in our body (Porges, 2023).

The secondary autonomic state, often referred to as ‘fight or flight’, is related to the triggering of the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) which functions to increase blood flow throughout the body to facilitate movement. When no threat is detected and we ‘feel’ safe the sympathetic nervous system can be activated to enable movement such as exercise or play.

The tertiary state, the newest development in the evolutionary timeline, relates to the activation of the Ventral Vagal Complex System (VVC), a component of the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS). Ideally, humans want to and hope to spend most of their time in the ventral vagus “window of tolerance” state, and only activate the primary or secondary protective states when confronted with genuine threats.

According to The Polyvagal Theory, the nervous system unconsciously perceives signals of safety or threat through a neural process termed ‘neuroception’ (Porges, 2009). Neuroception describes how neural circuits distinguish whether situations or people are safe, dangerous, or life threatening. Within this theory, three developmental stages of a human's ANS are described: immobilization (Dorsal Autonomic System), mobilization (Sympathetic Autonomic System) and social engagement (Ventral Autonomic System). All humans need appropriate social interaction strategies in order to form positive attachments and social bonds and a neuroception of safety is necessary before social engagement behaviours can occur.

The Polyvagal Theory provides a bio-behavioural explanation of how a therapeutic presence can facilitate a sense of safety in both therapist and client to enable a deepening of the therapeutic relationship and promote effective therapy. The Polyvagal Theory also offers insights into why a therapeutic relationship may impede a safe and effective therapeutic alliance. Cultivating a safe presence and engaging in person-centred relationships can therefore facilitate effective therapy by having both client and therapist enter a physiological state that supports feelings of safety, and therefore optimal conditions for growth and change.

The perception of safety activates the PNS, encouraging engagement, relaxation and connection, the key ingredients of a strong therapeutic alliance (Dana, 2018). Therapists who incorporate The Polyvagal Theory into their framework of practice will be less likely to blame or resent themselves or their clients for the unconscious activation of protective behaviours in a vulnerable setting. Without integration of The Polyvagal Theory into our practice we are missing the crucial role of neurobiological processes that can either enhance or impede change. Incorporating The Polyvagal Theory allows the therapist to track not only their client’s autonomic process but their own. It is the autonomic processes which are the mechanisms needed for insight and change.

At the heart of Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) is the exploration of the client’s emotional landscape which is maintained and perpetuated by Reciprocal Roles (RRs) and problematic procedures derived from past experiences with others. A necessary function of the therapeutic alliance is to provide a safe environment for the client to explore these painful experiences and emotions, however, if our client feels too frightened to permit, express, or even acknowledge their emotions it might be because they feel unsafe within themselves, or it maybe they feel unsafe with the therapist or the therapy environment. Educating ourselves and our clients about The Polyvagal Theory can help normalize these innate and understandable protective processes and our protective behaviours. Therapist genuineness and self-regulation of their own nervous system is a precondition to client safety to enable hard wired and unconscious ‘resistance’ to be soothed and calmed.

Following completion of an Introductory Training to CAT, I felt ready to undertake a CAT informed case with support and regular clinical supervision. I thought it would be reasonably straight forward to translate learning into practice – engage with client, listen carefully for their RRs and problematic repeating patterns and we’re off on our journey of recognition, revision, and change.

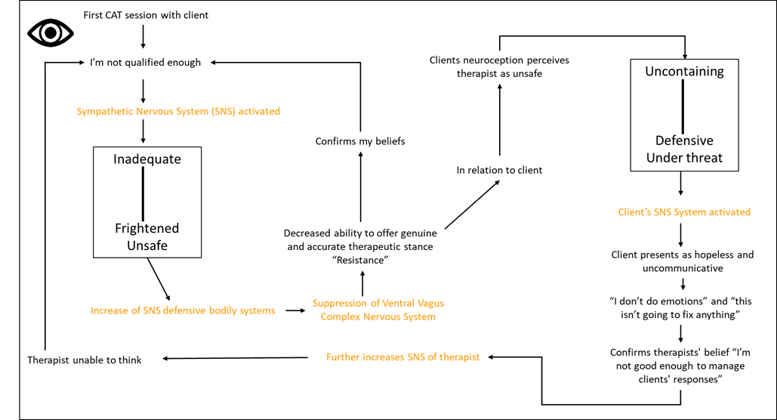

With my limited understanding of The Polyvagal Theory, I now realise that activating my Ventral Vagus ANS, the one that allows us to feel relaxed, sociable, and engaged, was an essential criterion prior to seeing my first client for CAT informed therapy. The need to feel calm and safe so I could convey a genuine feeling of safety and acceptance to my client was crucial if I was to engage my client’s Ventral nervous system. Unfortunately for my client, upon entering the therapy room the CAT model suddenly felt outside of my zone of proximal development, and I felt terrified of ‘doing it wrong’ or not being ‘good enough’. My dreaded imposter syndrome felt all consuming, activating my ANS and leaving it revving firmly in the Sympathetic state, rendering me cognitively and emotionally impaired. My self-to-self reciprocal roles (Inadequate – to – frightened and unsafe and Uncontaining – to – Defensive and Under Threat) impacted not only my ability to regulate my own emotions and make my client feel safe but prevented me from implementing the principles and tools of CAT. Bringing my fears and activated SNS into the therapy room meant I unwittingly created an unsafe environment and therefore signals of danger for my client, triggering their neuroception alarm system, creating an unsafe environment for both of us.

I naively believed a successful CAT therapy only required a client’s readiness to discuss their presenting problems and a therapist’s willingness to adopt an observing eye. How could I expect a client to feel safe enough to discuss their early experiences, fears, and core pain when I was constantly informing their neuroception alarm system, you are not safe because I don’t feel safe? Through clinical supervision I reflected on my own Reciprocal Roles, beliefs and fears about ‘doing’ CAT. Through a mapping exercise I was able to see how quickly and effortlessly I could activate my SNS and therefore the client’s, unintentionally putting us both firmly in the threat zone and unconsciously triggering or re-enacting my client’s past experiences.

My constant fear of falling into the client’s Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation (SDR) induced hypervigilance, fear, activation of my own snags and traps, and an inability to even notice when it was happening (Image 1). I was unable to provide my client with a safe and secure environment, let alone hear what the client brought to sessions.

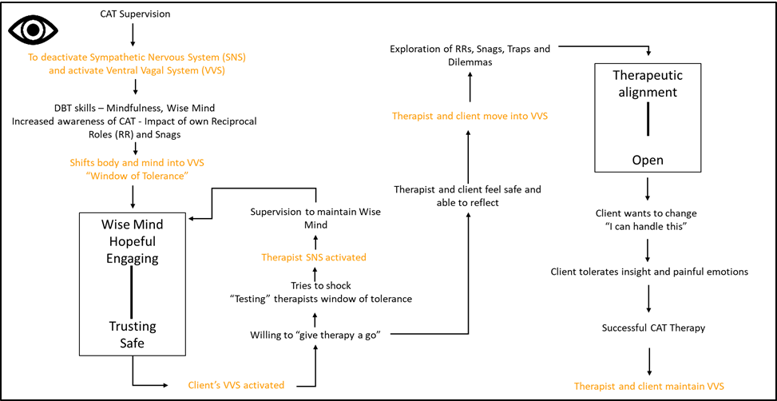

Disclosing and discussing my fears and reflections in clinical supervision, facilitated an understanding and appreciation of my fears and my focus on not falling into my client’s map, a behaviour that inevitably happened, time and time again. The RR and associated feelings of being inadequate to frightened and unsafe meant I brought anxiety and doubt into the sessions, thus increasing my own resistance. As a result, I was unable to provide a genuine therapeutic stance, confirming my beliefs that I was indeed not qualified to offer a CAT informed therapy. How could the client feel safe and supported if the therapist felt unsafe and uncontained? When The Polyvagal Theory was discussed in clinical supervision it all started to make sense and ‘exits’ from my own SDR to engage my Ventral Vagus Nervous System and down regulate my SNS became clear. Prior to each session with the client, strategies to calm my sympathetic nervous system and hopefully therefore my clients were introduced in the form of discussions on the clients and my own RR’s and problematic patterns and Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) skills including Mindfulness and Wise Mind (Image 2).

Understanding The Polyvagal Theory is helpful, even for those therapists able to enter their Ventral Vagus Nervous System easily, as a client’s neuroception is designed to scan the environment for threat, including anything in the therapy room or even phrases, certain behaviours or words used by the therapist. Asking a client to name one thing about therapy or the room they like but more importantly one thing they dislike, can reveal illuminating answers. A ticking clock, the box of tissues on the table, the fact that you let me through the door first or a word you use, may be surprising responses. The client’s neuroception, driven by external cues, is designed to detect threat and since threat is based on past experiences, anything is a possible trigger and therefore a possible threat to their ANS.

In my attempts to understand The Polyvagal Theory I was able to appreciate that I did not provide a safe and nurturing environment for my client to explore their experiences and naturally encountered ‘resistance’ from myself and the client. During the first few sessions, I felt my client was blocking me at every turn - blocking my attempts to enquire about their experiences, blocking my exploration of RRs and snags, blocking my insight, and ultimately blocking the activation of our Ventral Nervous Systems to allow emotional exploration. In hindsight I was the one who brought ‘resistance’ into the therapy space, unconsciously transmitting signals of fear and threat to my client. Given that many of our clients’ problems can be characterised by a nervous system that is alert to and biased towards feeling unsafe, it is paramount to ask ourselves “What can I do to make my client feel safe”?

My journey to becoming skilled in detecting and down-regulating my SNS in response to my own RRs, Traps and Snags is one I am still traveling; however, such reflective clinical supervision opportunities allow a space to breathe, to down regulate and therefore learn and grow – a space to understand and ponder not only the marvels of our biology but to acknowledge that our inbuilt ‘resistance’ is essential to our survival - the science of safety - and has to be acknowledged, welcomed and explored in order for change to happen. Miller and Rollnick (1991) say “the true art of therapy is tested in the recognition and handling of resistance. It is on this stage that the drama of change unfolds” (p. 112). Reframing resistance through a polyvagal lens - as unconscious protective processes and behaviour that are hard wired - can help us incorporate The Polyvagal Theory into CAT therapy to promote feelings of safety, so we and our clients have a robust ANS to deal with the next time life happens, as life will happen.

Alice Worley

Higher Assistant Psychologist

Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust

Windsor House

Harrogate

Supervised By

Dr Haydee Cochrane

Principal Clinical Psychologist

CAT Practitioner/Supervisor

CAT Lead for North Yorkshire and York

Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust

Windsor House

Harrogate

References

Dana, D. (2018). The polyvagal theory in therapy: Engaging the rhythm of regulation. W.W. Norton &

Company.

Geller, S. M., & Porges, S. W. (2014). Therapeutic presence: Neurophysiological mechanisms

mediating feeling safe in therapeutic relationships. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 24(3), 178–192.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive

behaviour. The Guilford Press

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. The Guilford

Press

Porges, S. W. (2001). The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system.

International Journal of Psychophysiology, 42(2), 123–146.

Porges, S. W. (2003). The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic contributions to social behaviour.

Physiology and Behaviour, 79(3), 503–513.

Porges, S. W. (2009). The polyvagal theory: new insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic

nervous system. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Porges, S. W. (2017). The pocket guide to the polyvagal theory: The transformative power of feeling

safe. W.W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment,

communication, and self-regulation. (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). W.W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S.W., & Porges, S. (2023). Our Polyvagal World: How Safety and Trauma Change Us. W.W

Norton & Company.

Ryland, S., Johnson, L. N., Bernards, J.C. (2021). Honoring Protective Responses: Reframing

Resistance in Therapy Using Polyvagal Theory. Contemporary Family Therapy, 44 (267-275).

Rogers, C. (1995). A way of being. Houghton Mifflin Co.