Agoro, D., 2024. Reflections on using 5 session CAT in a substance use service. Reformulation, Winter, p.21-24.

I am currently working in a service supporting individuals who use substances. Given the relational focus of Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) and the social relational impact of substance use, CAT has been pivotal in guiding the work I do. In this context, the flexibility of CAT means that everyone can benefit from this approach, through direct therapeutic interventions or staff consultations.

In the year ending 2022, 2.6% of adults aged 16 to 59 reported using drugs frequently (more than once a month), with cannabis being the most used drug in England and Wales (Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2022). In 2021, the UK recorded the highest number of alcohol related deaths on record, and the mortality rate has risen sharply since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (ONS, 2022). Nearly two thirds of those starting treatment report that they have a mental health need (OHID, 2021). Substance use has been associated with depression (Foster et al, 2016; Prestage et al, 2018), anxiety (Hines et al. 2020), reduced social network (Pettersen et al. 2019) and lower personal well-being (ONS, 2022).

When I started working in my current service, it became apparent that many of those who used the service faced difficulties in accessing adequate mental health support. The most common complaint was that service users were required to stop using substances altogether before they would be seen by mental health teams, with some services requiring them to be abstinent for a certain period thereafter. Unfortunately, this appears to be commonplace, whereby service users are excluded from mental health services, and substance use services are inadequately equipped to provide mental health support (Public Health England (PHE), 2017).

Following recommendations from the Dame Carol Black report (Home Office and Department of Health and Social Care, 2021), the government introduced a ten-year strategy aimed at reducing drug use (HM Government, 2021). The report highlights the need for local integrated pathways, to ensure that the physical and mental health needs of those who use substances are not overlooked.

I aim to work holistically with service users, recognising that they are much more than the substances they use. The integrative nature of CAT, and the fact that it has evolved from various theories and models, enables me to consider the individual from social, relational, and contextual perspectives. CAT is not posited as a diagnosis-specific intervention, rather it is a general psychological model, concerned with interpersonal difficulties and problems with self-processes (Ryle & Kerr, 2002). The collaborative nature of CAT, and the emphasis on seeing the client as a unique individual, allows CAT to be used in a range of settings, with clients of all ages, life stages and presenting problems (Corbridge et al. 2018). As such, I have found the adaptive and flexible nature of CAT conducive to working with individuals who use substances.

Although some individuals who use substances may not be appropriate for psychological therapy, this does not mean that they should be excluded from a psychological intervention. The structured and containing nature of the ‘Five Session CAT’ is particularly suited to such individuals (Carradice, 2013). This approach involves the client, therapist and care-coordinator working together to develop a relational formulation of the repeating patterns, to inform case management and subsequent interventions (Freshwater, Guthrie & Bridges, 2017).

In our work with clients, we do not focus on which came first - the mental health difficulties or the substance use. Instead, the focus is on how the two relate to one other. In most cases, clients will already be aware that they may use substances to manage difficult feelings or events. The ‘here and now' focus of CAT allows us to formulate this into a target problem procedure (TPP). This brings into conscious awareness an understanding of where the pattern emerges from, and how it presents throughout the day. For example, the client may expand their awareness from recognising that they use alcohol when they are stressed, to recognising that this comes from a desire to be accepted or loved, which is compounded by a belief that they are not good enough.

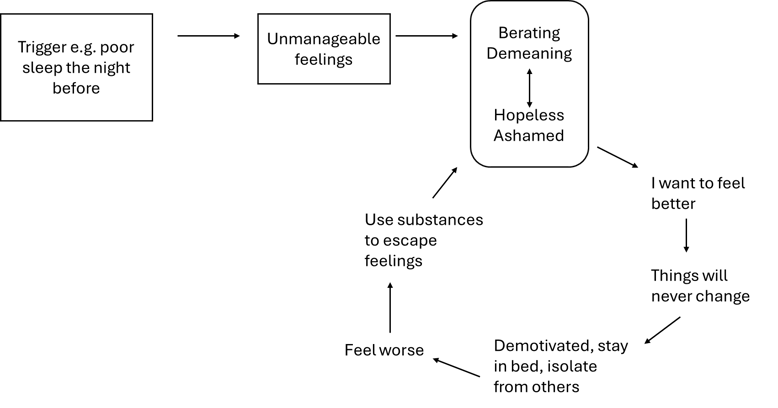

In the first session, we do the ‘the 24-Hour Clock’ exercise. This involves asking the service user to talk through the hours of an average day, to piece together their experiences and patterns of coping in the ‘here and now’ (Carradice, 2013). This is helpful as it enables us to piece together the different things that happen within a day, and how this may eventually lead to substance use. For example, a client may already be aware that they use substances when they are feeling low in mood, however, by exploring their day together, we can uncover the various nuances that may impact upon one another. We may come to recognise, for example, that if the individual has impaired sleep the night before, they may be less motivated in the morning, therefore less likely to adopt their usual routine and more likely to self-isolate. This in turn will lead them to feeling more depressed and therefore more likely to use substances. In this case, highlighting the impact of poor sleep not only helps us to understand the sequence of events, but also offers an opportunity to consider exits.

Figure 1: an example of how this may be represented in an Sequential Diagrammatic Reformulation (SDR):

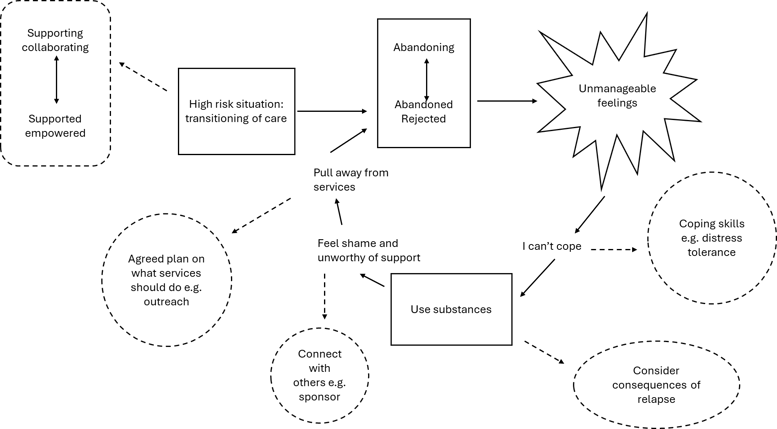

The SDR can also be a valid tool in supporting ongoing recovery and relapse prevention. Marlatt and Gordon’s (1984) model of relapse prevention highlights factors such as high-risk situations, lack of coping skills, and outcome expectancies, all of which can contribute to a relapse. The SDR can be used alongside this model to identify high risk situations that may lead to a reciprocal role enactment. For example, coming to the end of an intervention or episode of care is likely to provoke a range of feelings for different individuals. The SDR can be used to explore how the client might react to a transition.

For those who have experienced neglect and rejection, a common experience during a transition of care is to perceive the service as abandoning, resulting in the individual feeling abandoned and rejected. Their response may then be to disengage completely from services and/or use substances to cope with the unmanageable feelings. Together the client, therapist and recovery worker can recognise the procedure that may follow and ensure that exits are implemented in order to break the pattern. This may include making the transition more gradual and/ or ensuring that the client has something else in place when the intervention comes to an end.

Figure 2: an example of how an SDR with exits can be used for relapse

Working with the MDT

Working in a substance use service is challenging, and staff members frequently comment that they are continuously ‘firefighting’ when it comes to supporting those who access the service. The team includes managers, recovery workers, prescribers, and outreach workers. There are often multiple needs around housing, employment, social care, finances, criminal justice, and mental health. Mapping out reciprocal roles with members of the team allows us to notice the interactions that we may be pulled into.

The team who cares for those who access the service are committed to supporting them and are aware of the importance of the therapeutic relationship. As a team, we are mindful that many of those who use the service have experienced trauma and have been let down by others. This can result in a reciprocal role procedure of attempting ‘perfect care’.

The Boundary Seesaw Model (Hamilton, 2010) has been helpful in assisting the team to recognise that the desire to move as far away as possible from abusive and neglectful reciprocal roles, can lead them to unintentionally enact boundary violations on the opposite end of the spectrum. They may instead become the ‘Super-carer or Crusader’ and when we map it out, we recognise it as a ‘Rescuing to disempowered’ reciprocal role.

Upon reflection, team members are able to recognise these relational patterns, yet there is often a powerful fear of something going wrong, which in turn continues to drive the behaviour. We can then discuss exits around developing healthy boundaries, challenging threat-focused beliefs and moving towards giving service users more independence and responsibility. Ongoing clinical supervision is offered, with an emphasis on the therapeutic relationship and transference/ countertransference, so that team members can continue to reflect on how they work with others.

The key benefit of working with CAT is that it is adaptable and flexible, meaning that I can draw upon it in many ways within my role. I can use it with service users, individually with staff, or within team meetings. Although CAT is underpinned by various models, theories, and terminology (something which I have admittedly sometimes felt overwhelmed by), it does not have to be complicated. For example, when working and reflecting with staff, simply drawing out a reciprocal role can be enough to develop further understanding. As I continue to get to know the service and those who use it, I am keen to explore other ways in which I can use CAT, for example, in group interventions or reflective practice groups.

Dr Diane Agoro is a clinical psychologist and CAT practitioner who specialises in working with complex trauma and marginalisation. She can be contacted on dr.dianeagoro@gmail.com.

References

Carradice, A. (2013). ‘Five Session CAT’ Consultancy: Using CAT to Guide Care Planning with people Diagnosed within Community Mental Health Teams: Brief Summary Report, Reformulation, 41, 15-19.

Corbridge, C., Brummer, L. & Coid, P. (2018). Cognitive Analytic Therapy. Distinctive Features. Oxon: Routledge.

Freshwater, K., Guthrie, J. & Bridges, A. (2017). The experience of staff practising “Five Session CAT” consultancy for the first time: Preliminary findings. Reformulation, Summer, 59-62.

Foster DW, Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. (2016) Multisubstance Use Among Treatment-Seeking Smokers: Synergistic Effects of Coping Motives for Cannabis and Alcohol Use and Social Anxiety/Depressive Symptoms. Subst Use Misuse. Jan 28;51(2):165-78. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1082596. Epub 2016 Feb 4. PMID: 26846421; PMCID: PMC4755824.

Hamilton, L. (2010). The Boundary Seesaw Model: Good fences make for good neighbours. boundaryseesawbookchapter.pdf. Retrieved 27th November 2023.

Hines, L.A. Freeman, T.P., Gage, S.H., Zammit, S., Hickman, M., Cannon, M., Munafo, M., McLeod, & Heron, J. (2020). Association of high-potency cannabis use with mental health and substance use in adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, l77, 1044-1051.

Home Office and Department of Health and Social Care. Independent review of drugs by Professor Dame Carol Black (2021). Independent review of drugs by Professor Dame Carol Black - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk). Retrieved 20th November 2023.

HM Government. From harm to hope- A 10-year drugs plan to cut crime and save lives. 2021. From harm to hope: a 10-year drugs plan to cut crime and save lives (publishing.service.gov.uk). Retrieved 20th November 2023.

Marlatt, G.A. & George, (1984) W.H. Relapse Prevention: introduction and overview of the model. British Journal of Addiction 79, 261-275.

Office for National Statistics (ONS),(2022). Drug misuse in England and Wales: year ending June 2022. ONS website retrieved 27th March 2023.

Office for Health Improvement & Disparities (2021). Adult substance misuse treatment statistics 2020 to 2021: report. Adult substance misuse treatment statistics 2020 to 2021: report - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk). Retrieved 20th November 2023.

Pettersen, H., Landheim, A., Skeie, I., Biong, S., Brodahl, M., Oute, J. & Davidson, L. (2019). Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 13, 1-8.

Prestage, G., Hammoud, M., Jin, F., Degenhardt, L., Bourne, A. & Maher, L. (2018). Mental health, drug use and sexual risk behavior among gay and bisexual men. International Journal of Drug Policy, 55, 169-179.

Public Health England (2017). Better care for people with co-occuring mental health and alcohol/drug use conditions. A guide for commissioners and service providers. London: PHE; 2017.

Ryle, A. & Kerr, I.B. (2002). Introducing cognitive analytic therapy. Principles and practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.